Leverage is how consulting firms make money

As I discussed in a previous post, professional services firms – lawyers, accountants, marketers, consultants – are built on organizational pyramid structures. There are fewer partners than analysts, no surprise. The ratio of finders, minders, and grinders (senior, middle, junior resources) affects the types of projects they can handle and also their profitability.

Tall pyramids

Low leverage. In the consulting context, a tall pyramid is more likely the project staffing you need for a strategy or disruptive innovation project where the outcome is more ambiguous and open-ended. David Maister lovingly calls these “Brains projects” because they require the top minds of the firm who are typically the most expensive resources. In a legal context, I imagine patent strategy or high-stakes litigation would also be a “Brains project” where senior partners bill a lot of time to the client.

I find the that tall pyramid (low leverage) projects are usually more strategic, more intense, and shorter in duration. As a consultant, you learn an incredible amount about the subject matter and work closely with the partners and the rain makers. There is typically limited implementation. It is more work for the brain, less for the hands.

Flat pyramids

High Leverage. Maister calls these “Procedural projects” because they are very process-oriented. It is fairly clear what steps need to be taken, and junior resources can effectively do the work, if given good guidance. The average billing rates to clients will be lower, but these projects will also be more profitable because there is more leverage. These projects have a lot of on-the-job learning for analysts and consultants. This is where true apprenticeship happens. It’s a safe place to learn. The group dinners are fun, and there is a strong sense of team camaraderie.

One type is not better than the other

Over my career so far, I have worked on a mix of projects, both high and low leverage. Clients need both types of projects, depending on the scope, and the budget. Two examples from the same year, 2008:

- Low leverage strategy project: 1 partner: 1 manager: 1 consultant

- High leverage supply chain project: 1 partner: 4 managers: 15 consultants

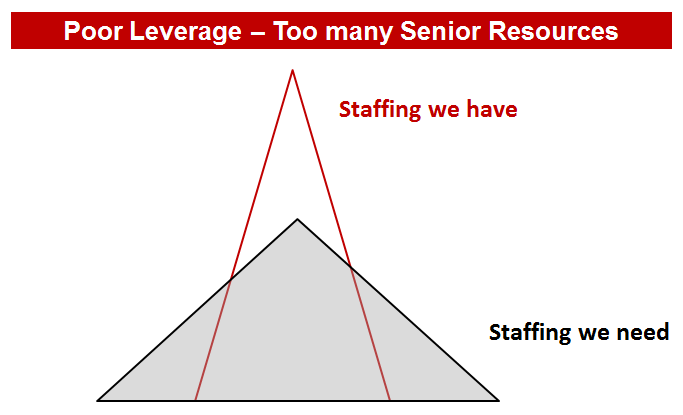

In the example below, the hypothetical firm has low leverage. Lots of partners and senior managers in relation to consultants and analysis. Very tall pyramid, so they can really only profitably take on strategic, high-paying work. If this firm were to win a larger project that required lots of junior resources, they either need to hire / contract newbies, or unfortunately, turn down the work. In consulting, you are either OVER-staff or UNDER-staffed. Hard to find the perfect middle in headcount or experience level.

For the Big 4 (where I came from), it’s very common for consulting firms to offer the client a low-leverage (tall pyramid) staffing structure during an assessment. The client gets senior resources during the assessment. Time is short, and the teams work into the nights. Great people, great work, great price.

Once the assessment is completed, and a road map for improvements has been created, the team usually evolves into a higher-leverage model with more consultants / senior consultants to implement the recommendations. A lot of the mental heavy lifting has been done – now it is a question of implementing the plan.

Incentives matter

Consulting firms are a bit notorious for the “up-or-out” methodology of forcing out non-performers and rewarding coveted promotions to only a portion of their staff. Unsurprisingly, the shape of the firm’s pyramid can change over time, depending on the type of work the partners sell, promotion guidelines, and retention. Once again David Maister is the gold-standard when it comes to firm economics, and he points out in his book Managing a Professional Services Firm:

“The mix of each that the firm requires (i.e., its ratio of senior to junior professionals) is primarily determined by the mix of client work, and in turn crucially determines the career paths the firm can offer.”

Having inexperienced people performing field work at a lower level of compensation may make for a increasingly profitable engagement, but is fraught with elevated risk of misinterpretation of data and misguided conclusions.

Definitely. And yet, that is the only way junior consultants get to learn too. It’s a trade off for sure.